‘Round the Mulberry Bush: Kids, food, and the hierarchy of needs.

By Lesley | October 12, 2011

Sesame Street has added a new muppet: Lily was introduced in an hour-long special entitled “Growing Hope Against Hunger”. Her purpose is to give kids in food-insecure households someone to relate to, as well as to draw attention to the issue.

…In the special, Lily is prompted to make a revelation when one of the more popular muppets — Elmo — remarks that he “didn’t know there were so many people who didn’t have the food they needed.”

Lily then confesses to him that she doesn’t know where her next meal is coming from and that times can be difficult.

Food insecurity is defined as the lack of a consistent access to food for active, healthy lives, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The USDA says 14.5% of households were food insecure at least some time during 2010 and that 5.4% of households experienced very low food security the same year.

Obviously, current rates of food insecurity are a side effect of the economic climate and continued unemployment or underemployment, although obviously this is a problem for some families even when times are good for the majority of folks.

Last month, the state of Georgia launched a childhood obesity campaign that uses striking photos of fat kids as cautionary tales, candidly relying on stigma as a body-shaming tool. There are billboards and commercials and it’s all very, very sad. (Thanks to Kyle for the images.)

In one commercial, a young girl says, “I don’t like going to school, because all the other kids pick on me. It hurts my feelings.” She is shot in stark greys, her expression blank. When she finishes speaking, a legend appears onscreen with a somber, booming flourish: “Being fat takes the fun out of being a kid.”

The next suggestion? “Stop sugarcoating it, Georgia.”

Meanwhile, in my home city of Boston, a campaign against “sugary” drinks (I have never fully understood how much sugar must be necessary for a drink to qualify as “sugary”, myself) features a commercial designed collaboratively with teens.

In it, a young man stops for a soda after seeing a girl walk by with a sports drink. As he takes his first sip, a blob of curious yellow material — it looks like lemon jello — flies into the frame and slaps him on the face. The commercial instructs, “Don’t get smacked by fat!” and then notes that sugary drinks cause obesity and type 2 diabetes.

There is one comment on the YouTube page, and it reads: “The thing is… it hasnt caused any of this to me…. so [I’ll] just keep enjoying my soda.”

It’s hard to imagine anyone taking childhood hunger seriously in the current atmosphere, in which childhood obesity is the popular drum to beat, but these issues are not so far apart as we might assume. It is certainly true that you cannot tell a child from a food-insecure household simply by looking at him or her. It is also likely, statistically speaking, that at least some of the children in these households are above the assigned weight for their age.

Like food insecurity, obesity is something that happens more frequently in poor households, although the precise reasons for this remain unknown. I would argue that it is related to a lack of access, both to affordable foods necessary for a balanced diet, as well as safe places for kids to be active. In the Georgia advertisements, these heartbreaking kids talk again and again about being picked on, and frankly being picked on does make it difficult to participate in group activities that might result in fun exercise.

In my own experience as a fat kid, I stopped playing sports not because I disliked them, and not because I could not play them, but because I was repeatedly told by my peers that I was not entitled to enjoy sports, or to be good at them. Because I was fat, and fat kids get picked last.

Georgia’s ad campaign is especially destructive because it underscores the very mechanisms that keep kids from being happy, healthy, and active, no matter their size — it reinforces stigma by portraying these kids in their dull grey worlds with their depressing words and their firm belief that no one likes them. Being fat does not take the fun out of being a kid, but being bullied by peers and adults certainly does.

The Boston “Fatsmack” commercial is equally troubling, for different reasons. It implies that consuming sugar actually causes type 2 diabetes, when there is no scientific evidence to support this claim. Indeed, you cannot simply eat your way to diabetes; while fatness is an associated factor, it is not a universal one, as vast numbers of fat people never develop the disease, and many non-fat people do develop it. A lack of physical activity is a much clearer risk factor for type 2 diabetes, but it’s far easier and more satisfying to scapegoat a particular food as the source of the diabetes scourge, isn’t it.

And of course, with the solitary comment, we see that such campaigns unwittingly send the message that sugary drinks or the smacking “fat” is only of concern when it results in obesity.

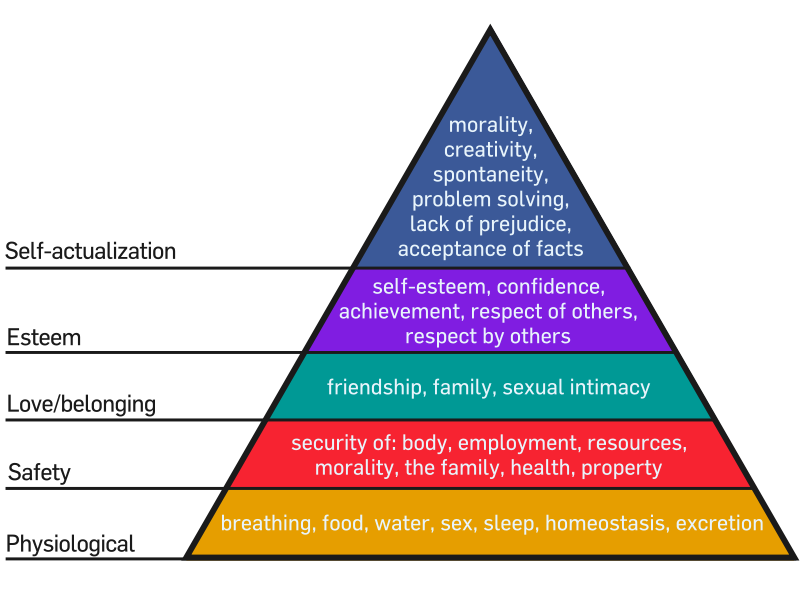

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a pyramid-shaped psychological model that specifies the things humans need to thrive and be healthful, in order of importance. [Edit: Certainly, there are many criticisms to be made of this theory, but I’m going with it for the visual and to get us thinking.] The base of said pyramid is comprised of physiological needs: the absolute minimum requirements a human requires to survive.

It includes food. According to Maslow, food comes before security, before family, before friendship, before self-esteem, before creativity. If we are to do anything else other than simply exist, first we require food, specifically enough food, in order to keep ourselves alive. Ideally, we should be secure in our food sources.

Kids in food-insecure households are stuck here, at the base, because not being sure of where or when your next meal will come, or what it will be — that distracts a person from focusing on much more than that. Especially a child with a limited ability to acquire food independently of a parent or guardian.

But many fat kids are stuck here too. They are stuck here because they are being repeatedly told that they are not consuming food in the proper way, or that they are eating the wrong kinds of food. Fat kids in food-insecure households may well be overeating when food is available because they are not sure when they will have that luxury again, and fat kids who do have reliable access to food sources are encouraged — or even forced — to resist their hunger (or whatever drives them to eat) in the name of “improving” themselves so they will no longer warrant being picked on — when really the problem is with a culture that allows fat kids — or disabled kids, or sick kids, or poor kids, or any kid who is persistently different — to get picked on in the first place. This is not how you teach a child to value him- or herself enough to eat in the way that makes them feel good, and healthy according to their own experience thereof.

By raising our kids to be obsessed with food, either the lack of it or the overabundance of it, we are stunting their development. We are holding them at the base of that pyramid instead of encouraging them to climb. No child should go hungry, ever, but nor should any child be made to feel stigmatized or guilty for eating. It does not work. It only produces kids who cannot fathom a world in which they will ever feel safe, and loved, and accepted, and real.

Two Whole Cakes is a blog written by

Two Whole Cakes is a blog written by

42 Comments