Reprint: Why the world needs fat acceptance.

By Lesley | July 25, 2011

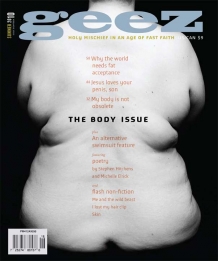

The following was originally printed in the Summer 2010 “Body Issue” of Geez Magazine, a Canadian publication dealing with progressive spirituality. I just learned last week that it actually won something: 1st place opinion piece in the Canadian Church Press awards. Wild, huh? Anyway, that reminded me that the full text of the piece never did make it online, so I’m reproducing it here.Â

The following was originally printed in the Summer 2010 “Body Issue” of Geez Magazine, a Canadian publication dealing with progressive spirituality. I just learned last week that it actually won something: 1st place opinion piece in the Canadian Church Press awards. Wild, huh? Anyway, that reminded me that the full text of the piece never did make it online, so I’m reproducing it here.Â

When I was in the sixth grade, there was a boy in my class who was continually trying to put his hand up my shorts.

It was like a compulsion. His desk was beside mine, in the very back of the classroom, so we were largely unsupervised most of the time. I’d be sitting at my desk and I’d feel someone touch my knee, or the bottom part of one thigh. At the time I was too young, or too naive, to know that I should report this to a teacher. I was however old enough to believe I was somehow at fault, and that his efforts to touch me were embarrassing, even shameful. I took to surreptitiously punching the boy whenever his hand inched toward me. He was small for his age, smaller than I, and why he chose to harass me in this way, I’ll never know.

One day, after many months of foiling his groping attempts, I was called on in class, and had to stand beside my desk to give my answer. As I began to speak, I sensed his hand creeping toward the hem of my shorts, and up my leg. In one smooth movement, ferociously intent on keeping this problem from becoming the public knowledge of the whole class, I stepped backward, crushing his hand between my considerable rear end and the edge of the desk. He cried out in pain, and only when the teacher inquired as to what was going on back there did I turn to look at him with a calculatedly blank stare.

He went to the nurse’s office; I believe he may have had a minor fracture. I occasionally wonder what he told them by way of explanation. At any rate, he didn’t try to touch me after that.

I spent a lot of time as a kid, as many girls do, negotiating the boundaries of my body — the ones I could set, and the ones others would try to set for me. Growing up as a fat kid made this all the more complicated, as I also had to negotiate cultural messages about the abnormality and abhorrence of fatness, and the attendant idea that fatness in a person is ultimately a symbol of a lack of self-control and/or moral character. As a fat kid, I knew my fatness made me bad, but I wasn’t clear on what I had done to deserve my fate. I’m not proud of the violence I perpetrated against that boy. It was the instinctive course of action, sparked by a rage I felt but couldn’t name. With violence, I might succeed in drawing a line. After all, by the sixth grade I’d already spent several years of my life perpetrating a kind of violence against myself, and my body, for failing to conform to my expectations, and the expectations of the culture in which I was living. My body had long been a site for battle.

I was dieting by the time I was eight years old, and though we now shudder in disbelief when we read studies in the news about kindergarteners who think of themselves as fat, and wonder what this world is coming to, it was already happening to me in the mid-1980s. Indeed, I had a keen awareness of my size even before that, but it was around age eight that I came to understand that there were few things in the world as terrible as being fat. As a child I’d sit in the bathtub, look down at myself, and envision neatly slicing away the small rolls on my belly. They were so unnecessary. Why couldn’t they just go away? I learned body-loathing early and I learned it well, well enough that it would take me into my twenties to learn to do without it. I dieted, and when my growing body unfurled knifing pangs of hunger through my every cell, I felt satisfied that I was succeeding. Certainly, the pain meant it was working. I was drawing a line.

We are all participants, willing or no, in a culture that promotes and glorifies this kind of violence against ourselves, and which revels in that violence’s effects. Even the language we use in discussing our body fat is steeped in violence; our fat parts are to be burned, blasted, destroyed, dissolved, eliminated, eradicated, or otherwise abolished. Let’s think for a moment about the broader effects of regarding our bodies—even an aspect of our bodies—with such language and imagery. This thinking divorces us from ourselves, and from the wonderful mechanism which enables us to experience the world. It creates a divide where none should exist. It turns our bodies into enemies, or antagonists, or discrete objects to be controlled and restrained. It denies us healthful connections between the thoughts in our heads, our interactions with the world around us, and the physical form that enables us to connect and communicate. It does us harm.

When I first discovered the idea of fat acceptance, one of the most powerful aspects was the reclamation of sovereignty over my body, and the radical notion that hating myself for failing to be thin was not compulsory, but optional. The alternative was acceptance. Certainly, acceptance is not the popular choice. Being a fat person who is no longer invested in weight loss is choosing a life as an affront to nearly everything culture teaches us about “taking care” of ourselves. Fat people are accused of letting themselves go, failing to take interest in their appearance, or even, with the ultimate dramatic flourish, flirting with suicide. All of this takes place in an atmosphere in which our bodies are increasingly considered public property, open to criticism and debate by an entitled populace. People get angry about fat folks. Very, very angry. I’ve never understood the anger, but it’s there. Once you’ve thrown wide the windows and doors to this anger, the importance of acceptance becomes vividly apparent.

Fat acceptance is not simply about individual choices, though that is an important aspect, and it’s the one that tends to draw people in at first. For some of us, those who would identify as fat activists, it’s also about changing culture, and confronting the social pressures that seek to either depress us into fruitless dieting, or shame us into living as invisibly as possible. Every day that I get up, get dressed, and go out into the world, I am making the case that fat people have a right to exist, to participate in life, and to be seen.

Over the holidays last year, I was walking through the parking lot at my local mall. As I tried to hustle between the slow-moving cars to get inside and do my shopping, I was cut off by a young driver who had decided I wasn’t worth stopping for. A voice from the carful of teens shouted at me: “Jesus, you’re fat!” People love to yell these things from cars. I expect it’s the drive-by aspect that’s so appealing; even if I am of a mind to defend myself, they can deny me the opportunity, because by the time I’ve spoken my response, they’re already gone. This, too, is violence of a sort, a shot fired at my self-esteem, my right to be out in the world, unashamed, meant to take me down a peg or two, to remind me that some portion of the people whom I assault with my corporeal presence on a daily basis are disgusted by me.

This is just something I have to accept, if I’m going to go about my life being fat and persistently visible. It’s a part of my day. But because I know these comments are explicitly intended to drive me underground, they actually serve as inspiration for me to be more ostentatious.

In this case, in that mall parking lot, the teens’ escape was cut off; the car in front of them had stopped to allow a mother with two young children to cross the street, in that slow, thoughtful way that young children do. The kids in the car who’d thrown their insult had nothing else to add; once you call someone fat, you’ve played your hole card. What is there to say after that? Everything else pales. I smiled. I walked around the front of their car slowly. I swung my hips. Then, once I had my back to them I planted a deliberate and unhurried smack of my hand on my own ass. Grinning at first, and then laughing audibly, I entered the mall.

If I am to value myself, and my intelligence, and my contributions to the world, I must also value the vessel that enables me to engage with that world, and that helps me to experience everything that makes me the person I am, no matter how anyone else may try to tear me down. And if I am going to expect others to respect and value my body and my choices, I must value the tremendous diversity of all bodies in return. Fat acceptance isn’t just for me, or just for fat people; everyone needs fat acceptance, because this is a lesson that benefits us all.

Fat acceptance doesn’t simply advocate in favor of fatness. Fat acceptance is also about rejecting a culture that encourages us to rage and lash out at our bodies, even to hate them, for looking a certain way. It’s about setting our own boundaries and knowing ourselves, and making smart decisions about how we live and treat ourselves, and ferociously defending the privacy of those choices. It’s about promoting the idea that anything you do with your body should come from a place of self-care and self-love, not from guilt and judgment and punishment. It’s about demanding that all bodies, no matter their appearance or age or ability, be treated with basic human respect and dignity. That’s the world I’d like to build. For all of us.

Two Whole Cakes is a blog written by

Two Whole Cakes is a blog written by

32 Comments