Fat Film Reviews: Gypsy 83

By Lesley | December 6, 2010

Gypsy 83 tells the story of Gypsy Vale, a 25-year-old Stevie-Nicks-obssesed goth girl working for her sister’s Fotomat and living with her musician father, well played by X’s John Doe, in the unremarkable nowhere of Sandusky, Ohio. Gypsy’s best friend is 18-year-old nascent queer Clive, a straight-A student who is apparently the only other goth in town. Clive’s parents are deceased, and he lives with his straight-laced but very supportive older sister. How Gypsy and Clive met is never revealed — obviously it wasn’t in school, given their age difference — but they share that deep platonic love that downtrodden outsiders who find one another and cling for dear life know so well. Both of them suffer daily harrassment at the hands of Sandusky’s residents, many of whom enjoy wearing pastel sweaters draped over their shoulders. Although both Gypsy and Clive have loving family, they are the only ones who truly understand each other.

One night, hanging out in Clive’s basement lair of draped velvet and posters of Morrissey and The Cure, Clive and Gypsy discover an annual Stevie Nicks tribute night in New York — the “Night of a Thousand Stevies†— and Clive announces they must go, so Gypsy can finally begin her long-delayed career as a rock star. Gypsy is stunned to see a picture of her similarly Stevie-Nicks-obsessed mother, who abandoned her and her father eighteen years ago, on the site advertising the event. Thus it follows that after some minor uncertainty, our two heroes set out on a road trip from Ohio to New York so Gypsy can perform, and potentially reconnect with her long-absent mom.

The film follows a fairly standard road-movie format, in which Gypsy and Clive stop off at various places to be harassed by the locals and to occasionally cry, dance, or learn a difficult lesson. Sometimes all of the above. Karen Black turns up in a brilliant performance as a tragic lounge singer named Bambi LeBleau; a pack of frat pledges being hazed appears twice. There is also a strange turn when the duo briefly adds a hitchhiking Amish runaway to their merry caravan, in a weird subplot that starts off trying hard to be quirky and then comes to an abrupt and loathsome end.

Gypsy is of a middling fatness, and her size is mentioned often in casual insults, to which Gypsy responds indignantly with such platitudes as “Big is beautiful, haven’t you heard?†That said, Gypsy is not above exhorting one jerk to “suck my fucking cock†in front of a packed bar in the very center of White America, all feathered hair and acid-washed-denim and Autograph’s “Turn Up the Radio†playing to a shuffling dance floor. Her exterior of self-assurance may not be undercut when she plods on a treadmill at home while watching herself in a mirror — there’s nothing wrong with keeping active — but her appearance of confidence suffers when she drinks a Slim-Fast for lunch, instead of, you know, actual food. Indeed, I’m not sure that we ever see Gypsy eat, though we do see her drink. In Gypsy’s one sex scene, she first asks if she can keep her dress on, but after being told how beautiful she is, decides to hell with modesty and gamely takes it off. Though she stands up for herself as a rule, at no point in the film do we ever get the sense that Gypsy has grown more self-accepting, and that’s a shame, as her bombastic assertions to strangers that she is fine the way she is would be more compelling if she herself believed in them. These criticisms aside, Gypsy’s size is not a huge part of the plot except in the few cases where she faces down haters, and there is no weight-loss redemption at the end.

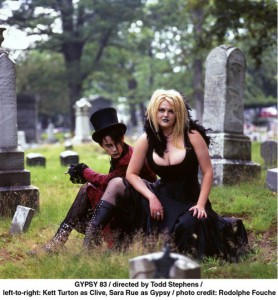

I found the goth angle in this story a bit more authentic and believable, and though it may not be a pitch-perfect image of how goth is done in more metropolitan areas, it does capture the mingling of dark glee and extreme awkwardness embodied by so many members of that scene. These are not kids just playing with 99-cent Wet n’ Wild eyeliner from the drugstore and tearing up black Hanes t-shirts to reassemble them with safety pins. The Sandusky Joann Fabrics has nary a single bolt of crushed velvet nor stretch lace that has not felt the gentle touch of Clive, who capably sews his own clothes, as well as many of Gypsy’s. Her outfits vary between romanti-goth and more Nicksian ensembles of cream-colored lace, while Clive is dressed in the classic goth sense, with a nice attention to detail, such as the ubiquitious bondage belt of o-rings and chains. (This, he must have bought online.)

Clive and Gypsy do attend to many stereotypes — they hang out in cemeteries, taking pictures of themselves and shooting spooky movies on super-8, they drink absinthe, and they goth-dance at every opportunity, be it in a public park or at a redneck bar (“pick the rose, smell the rose, throw the rose awayâ€). There are cheery montages to two of the most upbeat Cure songs ever recorded (“Just Like Heaven†and “Doing the Unstuckâ€). Everywhere they stop, they apparently first drape in velvet and fringe and surround with lit candles. This is eye-rollingly funny when it happens early on in a cemetery, but becomes ridiculous when it later takes place in a highway rest stop. If only it were done with the teeniest bit of self-awareness, or if we ever saw them gothifying a space before settling in to use it, I’d find this charming. Instead, it’s often distracting.

The film also explores Clive’s burgeoning queerness on their interstate journey. Prior to leaving Ohio, we learn that Clive is pretty sure he’s gay, though he’s not much interested in sex, and remains a virgin. Gypsy’s break with long-term celibacy in a rest-stop bathroom is twinned with Clive’s inevitable loss of virginity in the cruiser-friendly men’s room next door, and the two scenes are intercut almost so as to seem like one. His relationship with the slightly-older Gypsy is romantic in a platonic sense, and when he earlier asks her for an experimental fuck, just to be sure he’s gay, she kindly turns him down, saying she’s “been there†already. Later, when Gypsy halfheartedly apologizes for treating him appallingly after his bathroom encounter, he explains, “I thought I was in love with you, but I’m not. I worship you.â€

When Clive and Gypsy finally get to NYC, they go directly to the nightclub hosting the anticipated event, entering to the opening strains of Apoptygma Berzerk’s “Suffer in Silence.†It’s a great song, but it’s very much not goth, and it comes from an album that sharply divided old-school goths with those more accepting of synthpop and the burgeoning electronica scene. (And let’s just pretend that Apop ceased to exist after releasing Harmonizer, okay?) If Gypsy and Clive’s entrance were serenaded by Peter Murphy — or Andrew Eldritch, for that matter — then Clive’s wide-eyed and breathy acknowledgment that “We’re home,†would have had more impact, but Apop is what we get. Of course, once inside it’s not all darkness and dead roses, as Clive is hit on by a boy named Hazelton, and fails to know that “Poppy Z†refers to “Poppy Z. Brite†and that Lost Souls is a book and not an album, a misstep that gets him condemned as a poseur in a scene that feels more damaging than any of the other harassment this poor kid has received. Meanwhile, Gypsy discovers what’s become of her mother, and while we do get an answer of sorts, there is almost no explanation or resolution around her mother’s (and father’s) actions.

In the end, I’m not actually sure what this film means to be about. Is it about being a glittering freak in a dull mainstream world? Is it about Gypsy and Clive’s intense friendship? Is it about Gypsy’s search for her mom, and ultimately, herself? Is is about coming out and coming of age? Gypsy 83 attempts to touch on all these themes but never really satisfies on any of them. Clive and Gypsy reach their destination, but they don’t seem all that different for it. The final scene is, sadly, downright weak, and a plot point mentioned several times — Clive’s inability to drive — is totally forgotten so that he can vanish into the sunset in a predictable conclusion.

What saves this film for me is Sara Rue and Kett Turton, who play Gypsy and Clive. Today, Sara Rue is a Jenny Craig spokeslady and weight-loss advocate, but for this film I can forget all that and imagine that the Sara Rue playing Gypsy — sharp, hot-tempered, yet fragile — is someone else. Kett Turton is a standout as the exuberant and innocent Clive, so much so that he won the Best Actor award at OUTfest the year Gypsy 83 was screened. The chemistry and rapport between the two characters is magical, and feels as immediate as any of the intense friendships I had at that age. It is enough to even make up for the curious lack of actual Stevie Nicks music on the soundtrack — save a karaoke-esque cover version of “Talk to Me†— which was the result of the refusal by Nicks’ people to give over any of the rights. That said, this film is clearly a labor of love, and though it may lack a strongly-voiced message, the actors make it a story worth watching.

On Netflix and DVD.

Two Whole Cakes is a blog written by

Two Whole Cakes is a blog written by

13 Comments